Making Waves Again

It’s nearly 9 on a recent evening when playwright Tina Howe emerges from a white car and strides purposefully across the darkened plaza of the Old Globe Theatre, where her newest work is preparing to open. Six feet tall and elegantly poised in her trademark cowboy boots, the playwright glides toward her waiting appointment, a perfectly theatrical apparition in the foggy night air.

She is imperially slim, like E.A. Robinson’s Richard Cory, fashionably arrayed in flowing garments of black jersey and dark brown crushed velvet, with a black bowler hat crowning her blond pageboy.

For the record:

12:00 a.m. Feb. 2, 1997 FOR THE RECORD

Los Angeles Times Sunday February 2, 1997 Home Edition Calendar Page 91 Calendar Desk 1 inches; 21 words Type of Material: Correction

TV airdate--A profile of Tina Howe last Sunday gave an incorrect date for “American Playhouse’s” 1986 production of her play “Painting Churches.”

Reaching out, she extends a delicately boned hand in greeting. And if she is exhausted after a full day and evening’s worth of rehearsals, Howe doesn’t betray a trace of it.

Perhaps there’s something to be said for “good breeding.” That is, after all, the standard rap on this playwright.

“People perceive me as sort of a female [A.R.] Pete Gurney because of my background: New England, tall, fair, blueblooded with the last name of Howe,” says the soft-spoken yet intense writer, now seated in an upstairs theater office, discussing her work. “People are very comfortable when I play that role.”

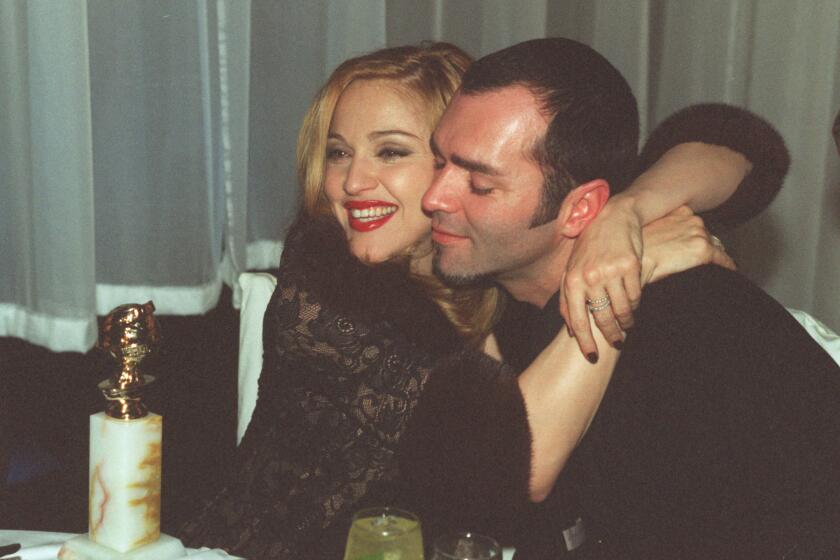

Indeed, that’s how she first won widespread acclaim. As the author of “Painting Churches”--a largely autobiographical drama about an adult daughter who returns home to help her upper-crust New England parents move out of their condo--Howe was part of a small group of female playwrights (including Marsha Norman, Wendy Wasserstein and Beth Henley) who broke through to new levels of commercial visibility during the 1980s.

Howe followed that success with the similarly genteel “Coastal Disturbances,” which played Broadway in 1987. And she has returned on occasion to mine her politely WASP niche since then, including with her latest work.

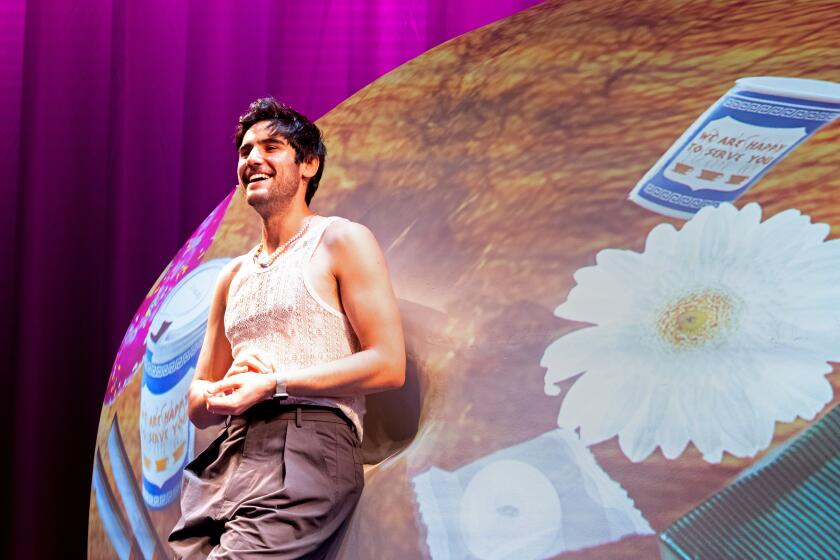

“Pride’s Crossing” premieres on Thursday at the Old Globe, directed by Jack O’Brien, the theater’s artistic director. The drama, which stars Tony-winning actress Cherry Jones in her first major stage role since “The Heiress,” focuses on 91-year-old Mabel Tidings Bigelow, a fictional former English Channel swimmer, as she looks back over her eventful life.

“Her plays reveal themselves from the inside, not from a structural or payoff point of view,” says O’Brien, who also directed the 1993 “American Playhouse” version of “Painting Churches.” “She is a kind of shy creature, and there is something of that elegant shyness in her plays.”

But there is more to the 59-year-old Howe than meets the mainstream eye. Beneath the bankably patrician veneer, a feminist absurdist lurks.

Her literary hero is Ionesco. She loves outrageous stage gestures--like having one of her characters dive naked into a huge wedding cake, only to be licked clean by a groom-to-be, as she did in “The Nest.” And she is given to “mischief.”

But Howe is well aware of the downside of being such a dramaturgical Jekyll and Hyde--particularly a female one. “Women playwrights have to walk a very fine line,” she says. “Most of us who have any degree of visibility are very aware of how far we can go in terms of technique or breaking the rules.”

Those limits apply to both form and content. “Whenever I’ve gone into dangerous waters, people get nervous,” Howe says. “When I go into my private self and do away with the class and the upbringing and go where danger lurks, it’s another story.

“Whenever I’ve written plays that have gone into the hearth or the bedroom or the kitchen and have really rejoiced in female behavior, the critics have run screaming out of the theater.”

And that, says Howe, is because sexism is alive and well in the American theater. “I don’t think women have been given license to really explore themselves on the stage,” says the playwright, who lives in New York with her husband of 35 years, novelist and NYU professor Norman Levy.

“When you get into the darker areas of female existence, because they are a novelty on the stage, it threatens,” Howe adds. “The theater is still basically a male bastion.”

‘Pride’s Crossing” may not send critics screaming out of the theater, yet it does go boldly where few plays have gone before--into the largely unseen world of an older woman’s life.

With the exception of a few Samuel Beckett plays and a handful of others--including such recent works as Emily Mann’s “Having Our Say” and Edward Albee’s “Three Tall Women,” which were written at roughly the same time Howe was writing “Pride’s Crossing”--it’s still unusual for an older woman to be the central character in a play.

That, in fact, is what first appealed to director O’Brien. “Pride’s Crossing” is about “aspects of women that don’t usually get dramatized,” he says. “Old-lady rage is not something you see on the stage very often.”

Set in the present with flashbacks to times as early as 1915, “Pride’s Crossing” captures Mabel Bigelow as she prepares to give a croquet party for her granddaughter. In the course of the preparations, Mabel flashes back to memorable moments in her own life.

The character of Mabel was inspired, in part, by Howe’s 89-year-old maternal aunt. “She did none of the things that Mabel did, and yet the play is very much inspired by how she dealt with the cards she was given as a woman of privilege growing up in a very small-minded community,” Howe says. Yet the protagonist is also closer to the playwright’s heart than may at first be apparent. “In fact, my given name is Mabel,” she admits, though only after more than an hour’s discussion. “But it’s such an awful name. I’ve legally changed it to Tina. But this is a secret that only I know--and now maybe the readers of the L.A. Times.

“The inspiration for the character is my aunt, but the story of the journey is my journey, because I did get out,” Howe says. “I got away from the world I was raised in.”

Brought up “in a very literary household” in New York, Howe is the daughter of former CBS radio newscaster Quincy Howe, himself the product of a family of literary and scholarly high-achievers. Her mother was also well placed in society, coming from a moneyed clan in Boston.

But Howe was daunted by the expectations of her heritage. Mostly, she remembers feeling awkward and inelegant.

“Because I was a ludicrous figure growing up--being 6 feet tall and weighing 3 pounds with glasses and buckteeth--I became the class clown,” Howe says. “I think the playwriting came from wanting to make people laugh with me before they laugh at me.”

She majored in political science at Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville, N.Y., but it was during those years that she also discovered her affinity for playwriting.

After graduating, she went to Paris to study at the Sorbonne for a year in 1960. “The great revelation was going to see Ionesco’s ‘The Bald Soprano’ at a tiny little theater,” Howe recalls. “Seeing that absurdist play was like walking into the living room of my own house. This is the world that I have been trying to pin down, and Ionesco did it.”

Howe returned to the United States and got married in 1961. But she didn’t forget the theater.

“My husband hadn’t finished his studies, so I had to teach high school,” Howe says. “So I began writing one-act plays for my students, and it was in those high school gymnasiums where I really learned my craft.”

When her husband was done with his studies, Howe began to get serious about her own career. Her first full-length play, “The Nest,” was produced at the Act Four Theatre in Provincetown almost as soon as she completed it, in 1969. “Then it moved off-Broadway,” Howe says, “but it closed in a night because Clive Barnes was so appalled.”

In fact, Barnes dubbed it one of the “10 worst plays” he’d ever seen. The farce about courtship included the coup de theatre of the naked woman diving into a wedding cake. Undaunted by the review, Howe was even bolder with her second play, “Birth and After Birth,” which she wrote between 1970 and 1973. To Howe, it dissects “the competition between women who have children and those who don’t, and how the women who have children brutalize the ones who don’t.”

“Birth and After Birth” was not staged for 23 years, and was produced for the first time only last year, in separate productions at the Woolly Mammoth in Washington and at the Wilma Theater in Philadelphia. Asked why she thinks it took so long, Howe replies: “It’s one thing for men to be absurdist, because they tend to write about power and identity, but for a woman to use absurdist technique with issues of child-raising or marriage, there’s something vaguely shocking about that.”

In the mid-1970s, Howe began to wise up. “The message got through to me that theater directors do not want to have their face shoved into the goings-on in the nursery or the kitchen,” Howe says.

The result was “The Museum.” Written with 44 formal roles, it was staged in 1976 at the L.A. Actors Theatre, performed by 55 actors. “It was a big success and Joe Papp came out and saw it and decided he wanted to do it in New York,” says Howe.

Papp staged the work at his Public Theatre in 1977, this time with a cast of 18, and took Howe under his wing.

Papp also presented Howe’s next work, “The Art of Dining,” in a co-production with the John F. Kennedy Center in Washington in 1979. Set in a trendy restaurant, the play required an elaborate staging that included the actual preparation of food.

But when Howe offered Papp the work that would prove to be her breakthrough, he passed on it. She took the play about the aging Churches and their grown daughter to Carole Rothman at Second Stage in New York, where it became a hit.

Yet in the years since “Painting Churches”--produced at the Old Globe in 1984 and South Coast Repertory in 1985--Howe has continued to move back and forth between her more conventional and experimental modes of writing, to predictably mixed results. Her next hit after “Painting Churches” was “Coastal Disturbances,” a romance set in Massachusetts that was nominated for 1987’s best play Tony. But that still didn’t buy Howe the creative freedom she wanted.

Her last work was “One Shoe Off,” an absurdist comedy about a long-term marriage that received negative reviews in an off-Broadway outing. But it will get its West Coast premiere at the Pacific Resident Theater Ensemble this spring at a date yet to be announced.

For “Pride’s Crossing,” Howe says, she was in the mood for something lighter. “It’s easy to be negative and to show how terrible life is and that people are betrayers,” Howe says. “But I do feel that a playwright should give an audience some hope, that our responsibility isto make order out of the chaos.

“This play is very much an antidote to the despair I feel in the air. I wanted to make a joyful noise.”

*

* “Pride’s Crossing,” Old Globe Theatre, Simon Edison Centre for the Performing Arts, Balboa Park, San Diego. Tuesdays-Saturdays, 8 p.m.; Sundays, 7 p.m.; Saturdays and Sundays, 2 p.m. $22-$39. Through March 2. (619) 239-2255.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.