- Minh Phan closed her restaurants and is the new artist in residence at Food Forward.

- The Michelin-starred chef is putting together an immersive exhibit and dining experience for the surplus-produce nonprofit.

It’s been over a year since Minh Phan closed her Los Angeles restaurants, but the refrigerator at her former Porridge + Puffs dining room in Historic Filipinotown is full. The shelves are crowded with tall deli containers filled with aqua blue passion fruit alginate, jet-black cardamom-and-coffee alginate, and jars of produce at various stages of fermentation.

Porridge & Puffs was Phan’s temple to rice, a pop-up turned restaurant where she took humble bowls of porridge and transformed them into some of the city’s most captivating dishes. She followed with Phenakite, her Hollywood fine dining restaurant, opened during the COVID pandemic in 2020. In its short tenure, Phenakite racked up the highest of accolades, including this paper’s Restaurant of the Year award in 2021, followed by a Michelin star. At one point, according to Variety, there were 20,000 people on Phenakite’s waiting list.

Yet Phan couldn’t help bumping up against the reality that the restaurant industry, always precarious, has been under tremendous stress since the pandemic, as evidenced by the avalanche of closures we’ve seen in Los Angeles in the past few years.

The word “porridge” means something different to everyone, conjuring bowls full of soupy spoon foods from every curve of the globe.

Phan is also the first to admit that running a business and managing people are not skills that come naturally to her artist’s persona.

In the newly released documentary “Food and Country,” directed by Laura Gabbert (“City of Gold”), Phan says that when she tried to even the disparity between kitchen staff and servers by paying both equally, she couldn’t find many servers willing to work for $20 to $25 an hour.

“I got a lot of criticism from people regarding why I shut down [the restaurants],” she says. “There were many reasons, but the work wasn’t serving what I want to do anymore. Food is ephemeral. “

In a recent podcast episode of Kenneth Nguyen’s “The Vietnamese,” she spoke of the ways we as a society view food.

“Why are we not looking at food like we look at museums?” she says. “And get grants?”

With these thoughts in mind, Phan decided that instead of focusing her attention on running another dining room, she would become the artist in residence at Food Forward, a nonprofit that recovers, then donates surplus produce from the L.A. Wholesale Produce Market plus other growers and produce shippers as well as leftovers from farmers markets and harvests from backyard trees. More than 250 hunger relief and community groups receive deliveries from Food Forward, which moves approximately 280,000 pounds of otherwise wasted produce a day through the Pit Stop, its 16,000-square-foot refrigerated warehouse in Bell.

“Minh and Food Forward share a lot of values and deep thinking around food and who gets to eat,” says Rick Nahmias, founder and CEO of Food Forward, now in its 15th year. “[This] is an opportunity for us to cross audiences and amplify the meaning of nutrition equity, food equity and building generational health.”

Nahmias and Phan met years ago and have been talking about working together in some capacity for a while now. The artist in residence role draws from Phan’s background as an artist, filmmaker and chef to help spread awareness for Food Forward’s food conservation efforts. Phan spent years in the film industry, building installations, working in graphic arts, writing, directing and doing art direction. She produced commercials and worked on numerous films including “Dazed and Confused,” “The Big Lebowski” and “Being John Malkovich.” For Glenn Kaino’s 2022 exhibition “A Forest for the Trees,” “about reimagining our relationship to nature,” as the artist described it, Phan created a teahouse where gallery goers could eat brown butter mochi and talk about their experiences in the gallery.

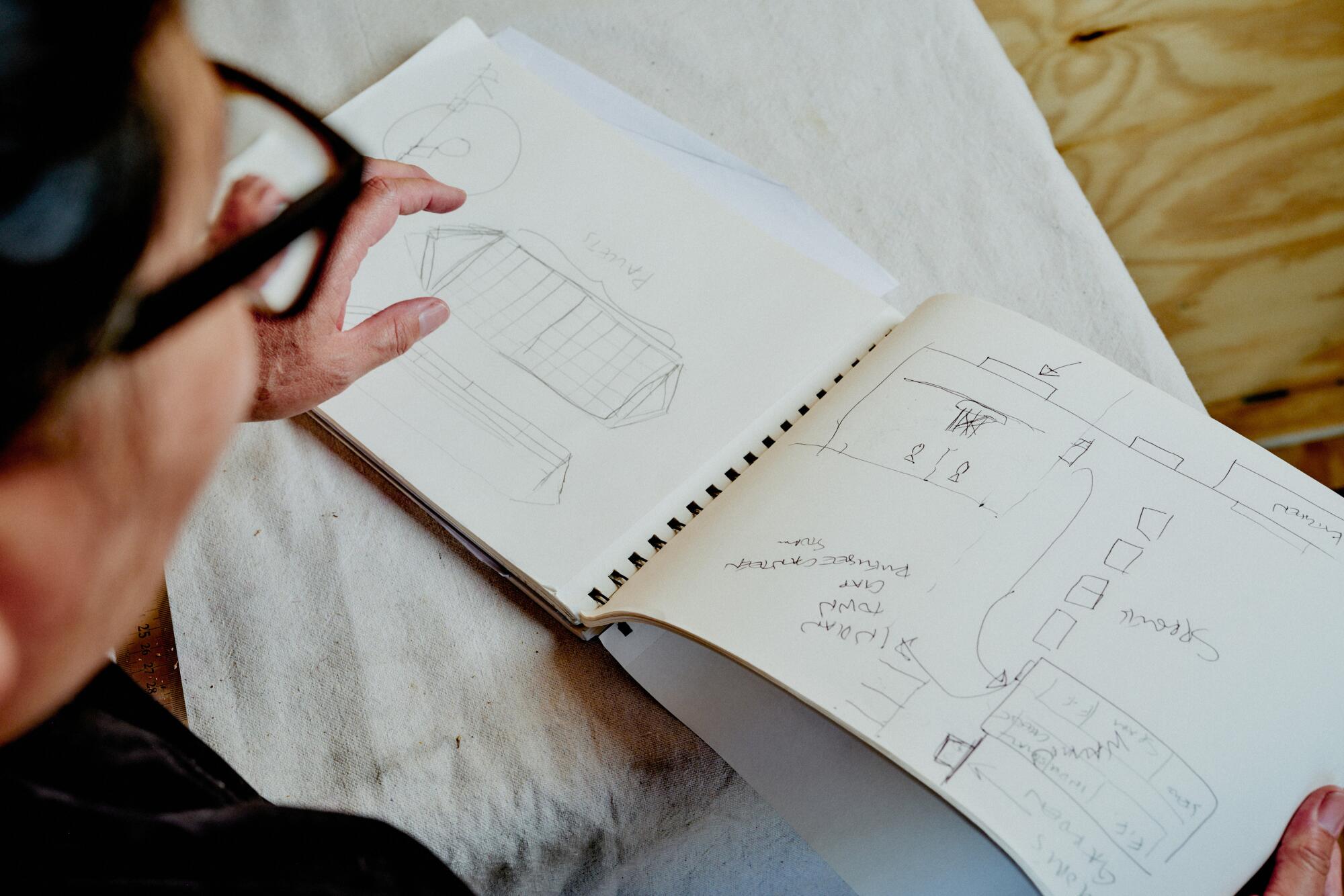

In her new role, Phan has spent the last several months creating an immersive exhibit that will be unveiled Oct. 19 at a ticketed event to benefit Food Forward. The evening will include a guided tour through an art exhibition that incorporates storytelling and a performance, and a seated meal that will evolve into what Phan is calling two backyard parties.

Materials for the show, such as wood boards, pallets and cardboard boxes, come from Food Forward’s Pit Stop warehouse. For the meal, she’s prioritizing seeds, peels, spent pulps and mashes that would otherwise end up in the compost, as well as seaweed, invasive wild mustards and radishes. Some of the produce will come from a list the Food Forward team calls “challenging” based on the difficulty some of the agencies and recipients experience trying to use them. Bok choy, snap peas and Buddha’s hand (fingered citron) are all considered challenging.

Phan’s initial mission was to find ways to repurpose food waste, exploring what she could do with items such as rotten fruit, the leftover mash of purees, and teas and coffee grounds. She also wanted to get certified to drive one of the forklifts that carry the pallets of produce. Her focus broadened when she noticed a number of tracks running along the floor of the warehouse.

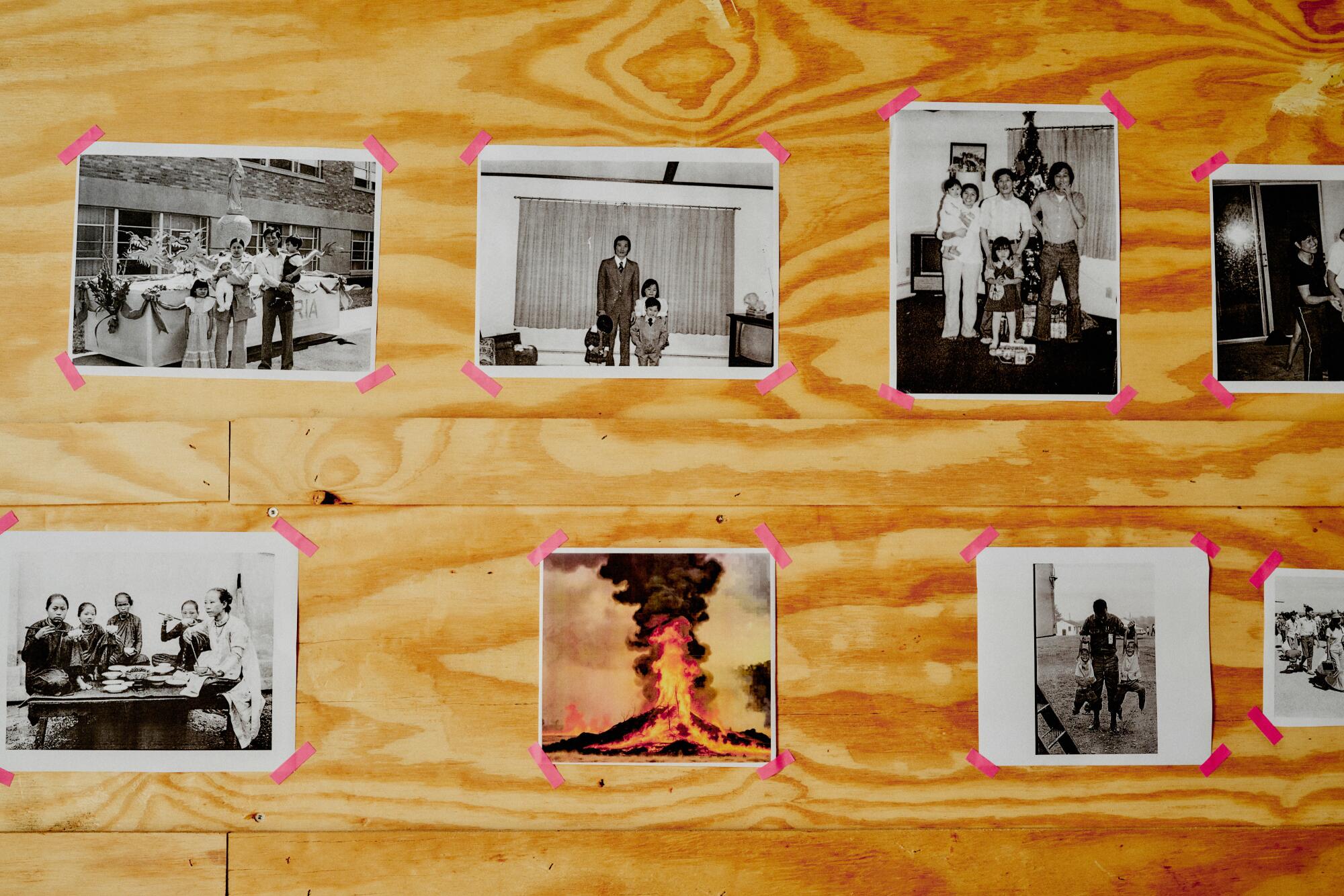

After researching the site, Phan found that the building was previously the Cheli Air Force Station, a place where bombs were tested during the Cold War.

“I come from bombs,” says Phan, whose parents fled Vietnam during the 1975 fall of Saigon, when she was 2 years old. “I wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for war, for bombs.”

“2025 happens to be the 50-year anniversary of Black April,” she says. “I came up with 10 different installations that I wanted to represent what Food Forward and the space meant to me.”

Each of the installations is designed to use Phan’s personal history to unlock the collision of war, one of the most unnatural things in the world, and the most natural act of feeding people.

“I’ve always expressed myself through sharing with others things that I care about,” says Phan. “In that sense, this [project] really bridges my work. I tend to really lean into the ethnographic questioning and interrogation of everything that I do and I think that’s the basis of a lot of my work.”

She’s using a trailer studio at the Pit Stop in addition to the old Porridge & Puffs space as an artist’s studio, workshopping materials and ideas for the exhibit. She brings over a small replica of a sailboat fashioned out of an empty Philadelphia cream cheese container and old business and membership cards.

One of the exhibits will represent the boat Phan imagines her parents and other refugees traveled on when they fled Vietnam. On the tracks where the bombs used to be assembled, Phan will build the boat, and fill it with the items a refugee would carry with them.

“There are only two things, food for the future and language and ideas,” she says. “Language and ideas you keep here and here, no one can see and you keep it as tight as you can.” She points to her head and then to her heart.

“And for food, you keep seeds,” she says. “I want to build a boat with food and seeds and I’m going to write poetry that I’m hiding on the boat to represent these boat people.”

Another installation, titled Indiantown Gap Refugee Canteen Storage, will turn the Pit Stop’s 2,000-square-foot cold walk-in storage into a mock food pantry of sorts filled with items made to look like Spam, Jell-O and industrial cheese. Indiantown Gap, Pa., is where Phan’s parents landed in May 1975.

“I want to drive home the point that without Food Forward, there would be no understandable food for other cultures, and that is the heart of what my work has been for the last few decades, trans-cultural understanding of ingredients and food,” says Phan. “By the very nature of Food Forward, it allows immigrants and those that are different to have a language of their own that’s not Spam, Jell-O or processed cheese.”

Phan is also recreating what she calls her mother’s trans-cultural garden. For the last 40 years, her mother has grown produce and medicinal herbs at the family’s home in Huntington Beach. Phan remembers her mother telling her to go into the garden as a child, and count how many leaves were on a specific tree, hoping the detailed task would help with her ADHD. She never made it to 100 leaves, but Phan’s time in her mother’s garden taught her about nature and the seasons, how things die and grow.

“I want everyone to have a trans-cultural garden,” she says.

The evening’s first course will be served from a garden Phan will create at the warehouse. She’ll also serve a version of the spring rolls her mother made her to take to a day of show and tell at her middle school.

“We were so poor, what do we show and what do we tell?” Phan says, remembering her family’s confusion. “This was Wausau, Wis., and I was the only person of color. My mom said, this is what our people eat, show them this.”

For now, Phan’s exhibit will only be on display Oct. 19, but her goal is to keep it at Food Forward and open it up to the public.

“So others get to know Food Forward,” she says, “and the work they do while think[ing] about immigrants, food insecurity, food injustice. ... It comes down to funding and logistics.”

Phan describes her relationship with Food Forward as perennial, and plans to deliver a guide book of sorts and recipe cards for how groups can use some of the lesser-known ingredients they receive from the organization. And she already has other installations she’s started working on, never having less than a dozen loose concepts in her mind at a time.

“I really want to collapse and integrate food into the art world so it gets preserved institutionally. The value of food and food workers is diminished a lot because we don’t value it as a cultural thing. ... I would like this work to be part of the zeitgeist.”

For more information or to purchase tickets to Phan’s Food Forward show and dinner on October 19, visit foodforward.org.

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.